Saranac Lake, nestled in the scenic Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York, boasts a rich history deeply entangled with the enigmatic ailment known as tuberculosis, or simply “TB.”

Tuberculosis peaked in the US during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, leading to the establishment of public health campaigns and the development of the BCG vaccine in the 1920s.

Antibiotic treatments for tuberculosis were created in the mid-20th century, with the introduction of drugs like streptomycin in the 1940s and isoniazid in the 1950s, revolutionizing the management of the disease.

But before modern science emerged with vaccines and treatments, people were desperately in search of cures for this deadly disease that during the 1800s killed one out of every seven people.

A plethora of dubious “miracle cures” inundated the market, lacking any solid scientific backing. Notable among these were the so-called “consumption remedies,” encompassing an array of products like herbal teas, elixirs, and tonics, all boasting the power to vanquish tuberculosis.

Surprisingly, or maybe not so surprisingly, substances ranging from heroin to alcohol were used in the pursuit of healing afflicted individuals.

In the relentless battle against tuberculosis in an era devoid of effective medical interventions, some rather drastic measures were also taken.

Over time, a prevailing practice encouraged individuals diagnosed with tuberculosis to uproot their lives and seek refuge in mountainous regions. These areas promised crisp, unpolluted air, abundant sunlight, and plenty of opportunities to reconnect with nature and the great outdoors.

As a result of this trend, patients began flocking to regions such as the Rocky Mountains, as well as other mountainous retreats like the Adirondacks in upstate New York.

In the heart of the Adirondack Mountains, Saranac Lake emerged as a focal point for the advancement of tuberculosis research and treatment, and at the forefront of this endeavor was the indomitable Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau.

Dr. Trudeau’s connection to tuberculosis was deeply personal. In 1876, he arrived in the Adirondacks, seeking refuge from the clutches of tuberculosis, a disease that had tragically claimed his older brother’s life within mere months of diagnosis.

During his sojourn in the mountains, Trudeau experienced a remarkable improvement in his health. This transformation inspired him to delve deeper into the therapeutic potential of nature, sparking his commitment to further research on the restorative power of the great outdoors.

In 1882, Dr. Trudeau stumbled upon the groundbreaking work of Prussian physician Dr. Hermann Brehmer, who achieved success in treating tuberculosis through what was known as the “rest cure” in the invigorating embrace of cold, crystalline mountain air.

Inspired by Brehmer’s work, Trudeau took the initiative and established the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium in 1885.

The Sanitarium embarked on its journey with a mere two patients treated in a one-room cottage named “Little Red,” which you can still visit today.

But the tide really turned when word of the therapeutic haven in Saranac Lake spread, bolstered by the endorsement of none other than Scottish novelist Robert Louis Stevenson.

Stevenson, the celebrated author behind literary gems like “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” and “Treasure Island,” once sought refuge in a Saranac Lake cottage in 1887. This historic abode has since been transformed into a museum teeming with artifacts that would captivate anyone intrigued by Stevenson’s literary legacy.

Ultimately Stevenson likely did not have tuberculosis. Still, he wrote a glowing review to the editor of the evening post in New York that likely helped bring considerable awareness to Dr. Trudeau’s efforts.

With heightened awareness and increased funding, the allure of Saranac Lake as a tuberculosis treatment destination became irresistible. A surge of patients flocked to the area, overwhelming the capacity of the Sanitarium’s cottages.

As a result, many individuals found solace and care in the charming, often family-operated cure cottages that sprang up in the vicinity.

In fact, Saranac Lake saw the construction of hundreds of these “cure cottages,” many of which still stand today in the form of residential houses or apartments, proudly earning their place on the National Register of Historic Places.

When you take a leisurely stroll through town, these cottages are unmistakable, featuring expansive “cure porches”– glass-enclosed rooms typically added to the ground floor of the house or crafted from existing house features. These rooms were equipped with sliding glass windows, offering precise control over the air circulation within.

You’ll find that certain cure cottages have been immaculately preserved, while others await the restorative touch of dedicated caretakers.

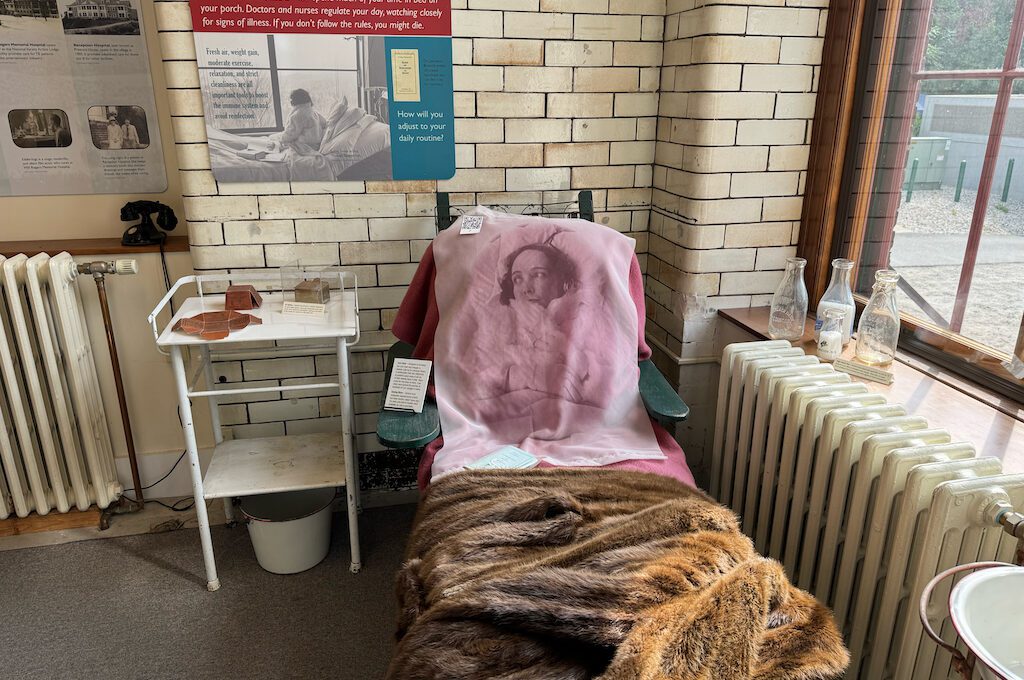

When checked into these cottages, patients adhered to a rigorous routine, spending at least eight hours daily on specially designed chairs and recliners (which might have even served as inspiration for the iconic Adirondack chairs).

For some, the path to recovery stretched over many years, making this curing process a patient and persistent journey.

Despite their battles with tuberculosis, many individuals residing in these cottages continued to live meaningful lives.

As the population seeking treatment swelled, various distinct communities began to flourish within Saranac Lake. There were cottages catering specifically to Greek, Cuban, and African American patients, as well as kosher boarding cottages tailored to the needs of Jewish individuals.

In some instances, families would take up residence in these cottages to provide support and care to their ailing loved ones.

In 1882, the pivotal moment arrived when German physician Robert Koch pinpointed and isolated the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis as the culprit behind tuberculosis. This discovery brought to light the contagious nature of the disease.

Consequently, Saranac Lake’s significance as a hub for curing tuberculosis was magnified, as many other destinations in the Adirondacks began turning away individuals afflicted with the disease. For this reason, many of those afflicted spent their remaining days in Saranac Lake.

In addition to his work at the sanitarium, Dr. Trudeau was deeply committed to advancing our understanding of tuberculosis.

To further his research, he took the initiative to construct a laboratory in Saranac Lake. However, in 1894, a devastating fire razed his modest laboratory to the ground. Undeterred, Trudeau rallied and established the Saranac Laboratory for the Study of Tuberculosis.

This pioneering institution marked the United States’ first laboratory dedicated to the study of tuberculosis, cementing Trudeau’s enduring legacy in the field.

Today, the original laboratory has been transformed into a museum open to the public.

Here, visitors can delve into the treatments and protocols that once defined Saranac Lake’s fight against tuberculosis. While it may be on the smaller side, the museum offers a treasure trove of artifacts from that era, providing an insightful introduction to the history of tuberculosis.

The laboratory’s legacy has now evolved into the Trudeau Institute.

The Trudeau Sanitarium ceased operations in 1954, thanks to the discovery of effective antibiotic treatments for tuberculosis. In 1957, Dr. Francis B. Trudeau Jr., the grandson of Dr. Trudeau, sold the sanitarium property to the American Management Association.

The proceeds from this sale were channeled into the establishment of a cutting-edge medical research facility on Lower Saranac Lake, which eventually became the Trudeau Institute, officially opening its doors in 1964.

Today, the institute stands at the forefront of research on major infectious diseases such as influenza, sepsis, and tuberculosis. It also delves into the intricate role of the immune system in conditions like cancer, asthma, allergies, arthritis, and multiple sclerosis.

Trudeau’s passing in 1915, at the age of 67, occurred well before the advent of antibiotic treatments. Nevertheless, he stands as a trailblazing figure in the realm of public health during the pre-antibiotic era.

From the outset of his work, he demonstrated a keen understanding of how crowding contributed to the transmission of diseases. Trudeau also championed the concept of isolation, recognizing its effectiveness in disease control.

He was an advocate for notifiable disease reporting and tirelessly promoted the virtues of fresh air, regular exercise, and a wholesome diet, imparting valuable lessons that continue to resonate in the field of public health today.

Dr. Trudeau’s enduring legacy is commemorated in a touching manner through a memorial located behind the Trudeau Institute building. It’s a poignant tribute, with the statue being a generous donation from his former patients. Remarkably, the sculpture was crafted by Gutzon Borglum, the very same artist responsible for the iconic Mount Rushmore.

Final word

A visit to Saranac Lake today offers a truly captivating and thought-provoking experience. Reflecting on the thousands who once flocked to this haven in the hope of finding healing, despite the absence of modern medical guidance, invites us to ponder the lives they led.

One can’t help but wonder about the thoughts that occupied their minds during those long hours of rest on those picturesque porches. With no certainty of a cure, their hopes, fears, and dreams likely ebbed and flowed like the winds rustling through the trees.

The appreciation they must have cultivated for the natural beauty of the Adirondacks is equally intriguing.

The moments when they could venture out to embrace the mountains and lakes, perhaps for the first time in their lives, must have been profoundly meaningful. These experiences could have offered solace, inspiration, and a connection to a world beyond their illness.

In many ways, a visit to Saranac Lake today serves as a poignant reminder of the resilience of the human spirit and the power of hope in the face of uncertainty. It’s a testament to the strength of those who sought refuge here, seeking not just a cure but also a deeper understanding of life itself.

Daniel Gillaspia is the Founder of UponArriving.com and the credit card app, WalletFlo. He is a former attorney turned travel expert covering destinations along with TSA, airline, and hotel policies. Since 2014, his content has been featured in publications such as National Geographic, Smithsonian Magazine, and CNBC. Read my bio.