The story of Stone Mountain is inseparably linked to a troubling history rooted in racist ideals—no way around that reality.

While this dark past has been extensively covered in articles, it’s worth revisiting for those unfamiliar with the details.

Let’s quickly delve into some key historical moments.

Back in the 1910s, there was a push to construct a Confederate monument on the mountain. Helen Plane, the driving force behind this effort, was not just a member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy but also a supporter of the KKK.

In 1915, atop Stone Mountain, William J. Simmons declared the re-establishment of the Ku Klux Klan in a solemn ceremony.

Following this, the Stone Mountain Confederate Memorial Association (SMCMA) emerged, aiming to bring Plane’s vision to life by carving a Confederate monument on the mountain’s side. Initially, they enlisted carver Gutzon Borglum, renowned for sculpting Mount Rushmore.

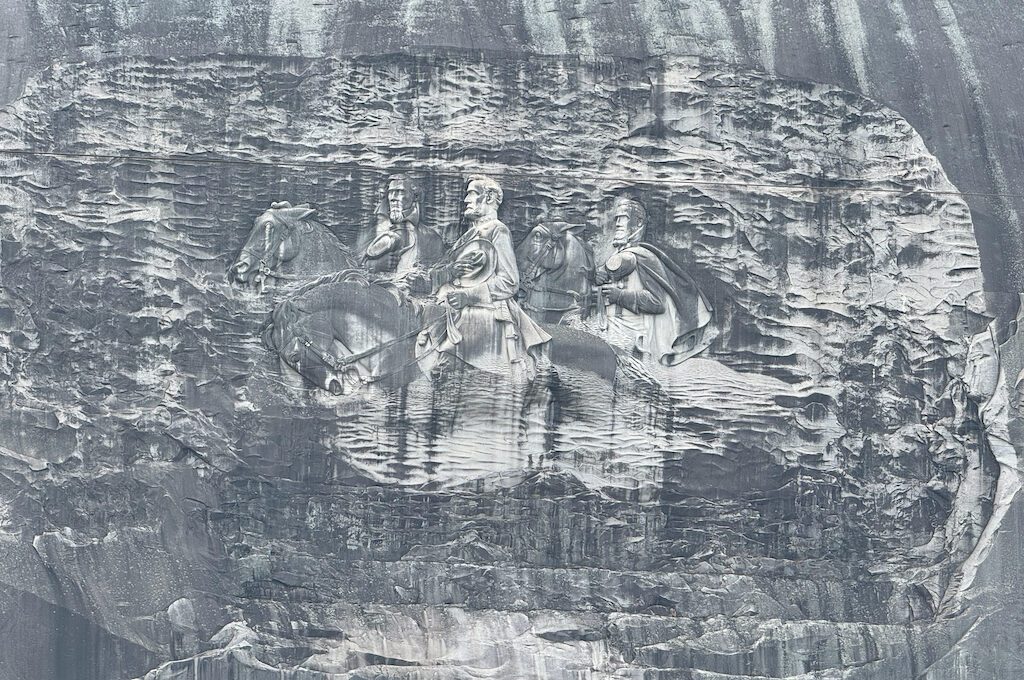

The project encountered setbacks early on. After parting ways with Borglum, the SMCMA decided to obliterate his work from the mountain. They then brought in American sculptor Augustus Lukeman, who successfully carved Robert E. Lee’s head and part of his torso before running out of funds amid the Great Depression, bringing the project to a standstill for several decades.

In the 1950s, gubernatorial candidate Marvin Griffin, a staunch segregationist, resuscitated the initiative, fulfilling a campaign promise. Griffin seized on the momentum generated by the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brown vs. Board of Education on May 17, 1954, which dismantled the legal foundation for school segregation.

During a campaign rally, he pointed to the mountain, vowing to complete the carving. It was only in 1970 that the monumental work was officially unveiled, marking the completion of this controversial project.

Given this tumultuous history, one might wonder if it’s time to dynamite the whole thing off the mountain. Well, that’s a complex question with no easy answer.

Here’s why I would argue Stone Mountain should stay

When you gaze upon that statue and roam its surroundings, it evokes a profoundly poignant experience.

You’re bound to have a visceral reaction of a particular kind. Some describe it as slightly unsettling, as if you’re standing in the shadow of historical malevolence.

While I didn’t personally feel that sense of creepiness, the encounter carried a tangible weight, almost surreal in nature. Thoughts of MLK’s mention of Stone Mountain in his “I Have a Dream” speech flooded my mind, and I got taken back to the turbulent battlefield of the Civil War — America’s bloodiest war.

It was the kind of discomforting reminder of the past that simply doesn’t translate through a photograph or even a museum exhibit.

I firmly believe that these experiences hold immense value and that we should actively preserve them, provided certain considerations are taken into account.

The initial consideration lies in how closely intertwined an object is with a past monstrous act. Human nature is intricate, and none of us exists solely in the realm of absolute good or evil. Criticizing historical figures through the lens of contemporary standards is tempting, yet it doesn’t always hold water.

I believe the bar should be set exceptionally high when it comes to demonizing figures from the past, largely reserved for those involved in truly monstrous acts that transcend our time differences.

One significant challenge in removing historical monuments today is that the connection to their “evils” is often too tenuous to warrant erasing a piece of history.

But is that the case with Stone Mountain?

While Stone Mountain stands as a Confederate memorial, it doesn’t parallel sites like Vicksburg, MS, where a massive battle claimed 30,000+ Confederate lives. Because of that, I think the “memorial” aspect of the mountain hardly covers for the undeniable link to the KKK in the early 20th century and anti-civil rights efforts from the 50s through the 70s.

But is the connection to these potentially “monstrous” activities strong enough to warrant the sculpture’s removal? I suppose it depends on who you ask. But regardless of where you fall on that question, I think the placement of the monument is an even more crucial factor here.

The context of the monument’s location plays a crucial role in shaping these encounters with history.

If a controversial monument is situated in a bustling area, forcing people into uncomfortable encounters, that’s one scenario. However, if it’s tucked away in a less-trafficked space, making the encounter entirely optional, the dynamics change significantly.

Stone Mountain doesn’t command attention in the midst of a busy intersection or even offer a visible presence from the highway, as far as my observations could tell. In fact, you can easily embark on a hike on Stone Mountain without catching a glimpse of the sculpture.

Creating a society where any inkling of offense prompts destruction might not be the path we want to tread. It sets a precedent of discarding history solely to maintain comfort, and I believe there’s value in facing the unpleasant aspects of our past.

This is especially true when individuals can engage with it on their own terms, as is the case with Stone Mountain.

There’s also an undeniable artistic value in the sculpture at Stone Mountain, despite mixed opinions. Personally, I found it quite beautiful up close, although from a distance, its aesthetic appeal diminishes in my opinion.

It’s crucial to tread carefully when considering the extinguishing of such significant pieces of art, even when their associations and origins are problematic. Relocating it to a museum or a more removed location is a typical solution, but the nature and scale of this artwork make that impractical.

Beyond its artistic value, there’s the modern day engagement with Stone Mountain to ponder.

Stone Mountain is a mini mountain getaway just outside of Atlanta, boasting breathtaking rocky terrain reminiscent of Enchanted Rock in central Texas but on a grander scale. The landscape includes enchanting canopies of pine trees and, of course, panoramic views, including the multiple skylines of Atlanta.

What’s truly remarkable is that people from diverse backgrounds visit this place, enjoying the sights and seemingly coexisting harmoniously.

It’s a space where individuals of different races come together, hiking side by side in a location that was once associated with the rebirth of the KKK. This suggests a form of healing emanating from this rock.

Shouldn’t we take that into account and acknowledge the positive transformations already occurring in this space? Is that not the most powerful form of extinguishing prior evils?

So what should be done?

If the sculpture remains, one approach could involve incorporating panels that candidly address its racist origins. These panels could provide historical context, acknowledging the complex narrative and the association with the KKK.

However, a complete overhaul of all the current panels might not be necessary.

I, for one, found it very interesting to read the panels from the perspective of someone memorializing Confederate soldiers. It was no different than reading interpretive panels discussing the battles and figures from, say, the Revolutionary War or the French and Indian War. But this was the Civil War.

While the instinct for some might be to introduce more modern or “woke” perspectives throughout the grounds, particularly countering the Confederate pride evident in the texts, there’s merit in maintaining the original Southern perspective.

Reading the signs from that viewpoint can offer a genuine understanding of their sentiments, fostering a nuanced comprehension that a generic neutral take would not achieve.

Regarding the idea of incorporating the image of someone like MLK into the sculpture, it’s worth contemplating, but we should carefully assess the potential impact. Modifying the sculpture runs the risk of diminishing its potency as a time capsule that encapsulates a specific era and message.

So where does that leave us?

Ultimately, Stone Mountain bears a deep and undeniable connection to racist ideals, particularly those associated with the KKK and anti-civil rights sentiments spanning the 1950s to the 1970s.

Some argue that it’s not merely a monument but a political statement. Even if Stone Mountain is viewed as a bigoted political statement, the fact that we have this perspective from that era preserved allows us to witness and critically reflect on it today—something we can do on our own terms due to its location.

Encapsulating that viewpoint for contemporary observers prompts crucial introspection and learning. My desire is for others to undergo a similar experience as I did when closely examining the sculpture and the surrounding memorials.

Wrestling with the conflicting emotions and feelings attached to it imparts humanity to the hundreds of thousands lost while also recognizing the regressive thinking that opposed the progress of civil rights for black people. It’s a complex encounter that encourages a deeper understanding of our shared history.

Daniel Gillaspia is the Founder of UponArriving.com and the credit card app, WalletFlo. He is a former attorney turned travel expert covering destinations along with TSA, airline, and hotel policies. Since 2014, his content has been featured in publications such as National Geographic, Smithsonian Magazine, and CNBC. Read my bio.