Certain historical events carry an irresistible intrigue, providing a glimpse into a bygone era where different rules and a sense of wild unpredictability prevailed.

The Crash at Crush Texas stands as a prime example of such captivating tales.

Join me on a journey to this historic spot as we unravel the details of this remarkable and somewhat wild story.

What is the Crash at Crush?

The Crash at Crush is a publicity stunt that took place on September 15, 1896, in Crush, Texas.

The stunt involved two uncrewed locomotives from the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad Company (M-K-T) intentionally crashing head-on at high speed. The impact caused the engine boilers of both trains to explode, killing two people and injuring many others among the 40,000 spectators.

Crash at Crush historical background

The Missouri, Kansas, Texas Railroad, fondly nicknamed “the Katy,” made its way to the Crush, Texas region back in the 1880s while forging a route connecting Dallas and Houston.

As the railroad expanded with a growing need for increased capacity and speed, it found itself with outdated steam engines after transitioning from 30-ton to more robust 60-ton engines.

In 1896, William Crush, an agent for the Katy, hatched a unique plan for dealing with those surplus obsolete trains.

He envisioned turning it into a grand publicity stunt by orchestrating a spectacular collision of these outdated locomotives.

Interestingly, he wasn’t the pioneer of this concept. A similar locomotive crash had already captivated audiences in Ohio in May 1896, proving to be a massive success. So naturally, Crush drew inspiration from the earlier event to bring his own version to life.

Attendance for the event was complimentary, mirroring the approach of the successful crash in Ohio.

Rather than relying on ticket sales, the ingenious plan involved capitalizing on special excursion trains. These trains offered round trips from various locations across the state, priced at around $125 in today’s currency—an enticing package deal for spectators traveling to and from the crash site.

The promotional engine kicked into gear, and the event received extensive promotion. Both locomotives slated for the crash were showcased in a touring exhibition and the event garnered widespread attention, with even Thomas Edison dispatching a photographer to capture the spectacle.

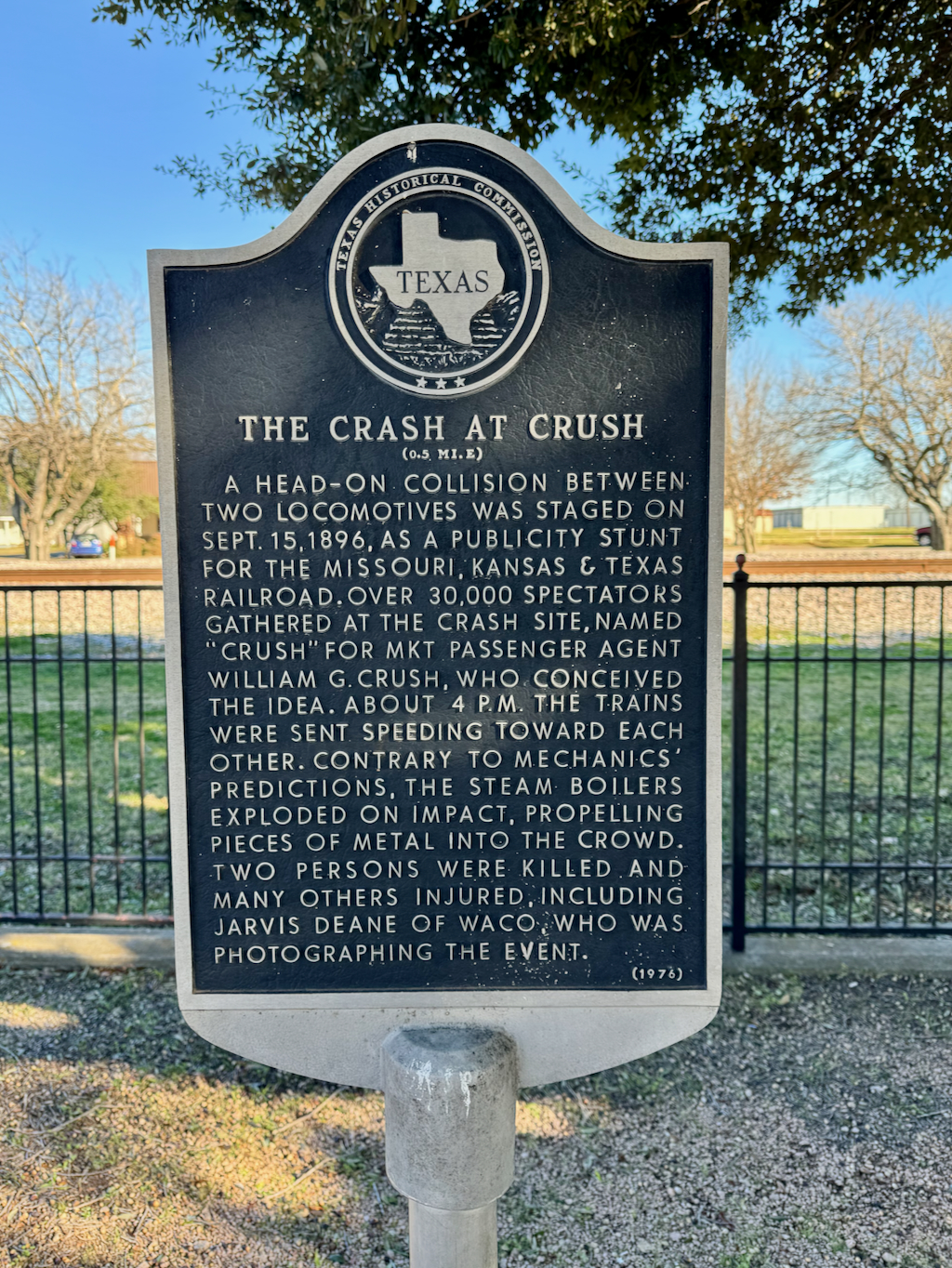

On September 15, 1896, the temporary town of Crush, Texas, (named after William Crush) transformed into a bustling scene.

The site boasted a grandstand and speaker stands. Adding to the carnival atmosphere, a Ringling Brothers Circus tent was pitched, telegraph offices were set up, and a dedicated train depot emerged for this ephemeral city.

Vendors lined the scene, offering everything from carnival games to cigars and lemonade. A special police force of 300 was brought in.

To prepare for any unexpected outcomes, a separate four-mile stretch of track was laid alongside the Katy Railroad, ready to handle a potential runaway train.

The setup featured a track segment atop low hills on opposite sides of a bowl-shaped valley, offering a gentle slope that we observed when visiting the actual collision site.

Prior to the collision, safety measures were implemented, including speed tests conducted with engineers to pinpoint the precise collision point.

Assurances were given that all safety precautions had been taken. A safety perimeter of approximately 200 yards was established for the general public, while members of the press were granted closer access, allowed to stand within 100 yards of the track.

Despite Katy officials expecting a crowd of around 20,000, the months of marketing efforts drew an impressive 40,000-strong audience, with people coming from all over the country. This made Crush, Texas temporarily the second largest city in the state.

As the collision time approached, crowd control became a challenge. The event faced delays as eager spectators attempted to inch closer, prompting police intervention to maintain a safe distance.

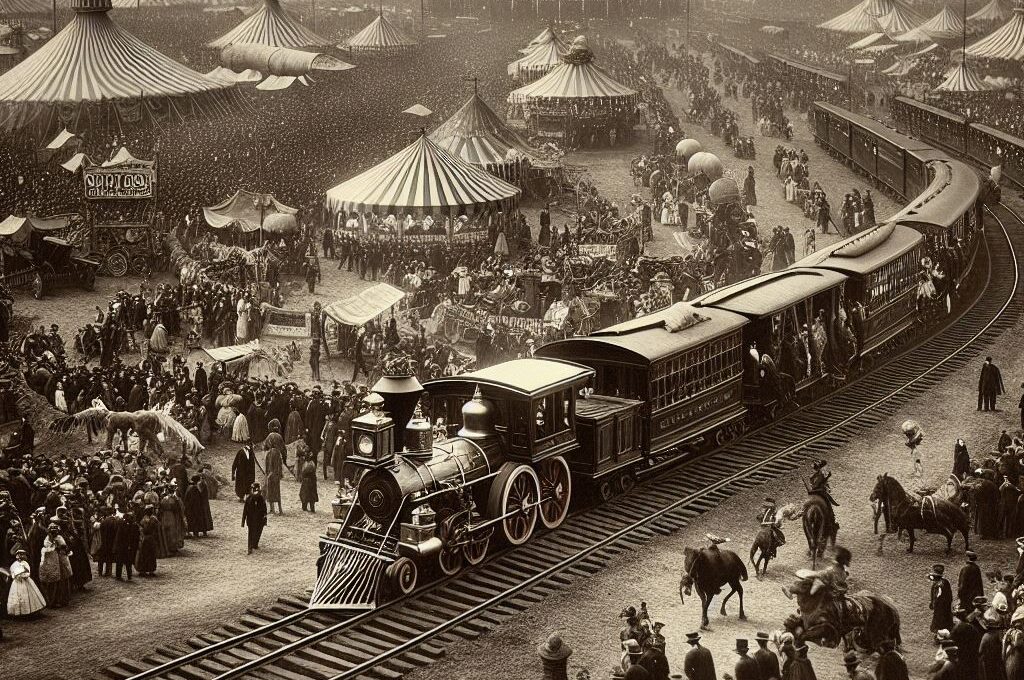

Around 5:00 p.m., the two trains, hauling cars loaded with railroad ties, convened in the middle of the track for pre-crash photographs. The visual spectacle included two locomotives, No. 999 painted in green with red accents, and No. 1001 painted in red with green highlights. The trains were followed by seven cars adorned with sponsors, including P.T. Barnum’s circus and the Orient Hotel in Dallas.

Subsequently, they were rolled back to their starting points at the ends of the track within the slight valley. William Crush, making a dramatic entrance on a white charger, signaled the commencement of the crash.

The Dallas Morning News vividly captured the unfolding spectacle, detailing the trains’ crescendoing approach at 50 mph, their whistles blaring, and the detonation of torpedoes placed on the tracks.

The rumble of the two trains, faint and far off at first, but growing nearer and more distinct with each fleeting second, was like the gathering force of a cyclone.

The collision itself was followed by a moment of eerie silence, abruptly shattered as both boilers exploded simultaneously, creating a dramatic and unforgettable climax to the event.

The collision unleashed a storm of flying shrapnel, varying in sizes from iron fragments to more substantial pieces.

Chaos and panic ensued among the thousands in attendance, and tragically, the flying debris claimed two lives and left at least six others with severe injuries (some say 3 were killed).

The account of a Confederate veteran who witnessed the crash likened the scene to a Civil War battle.

Photographer Jarvis “Joe” Deane from Waco, in his attempt to capture the wreckage, paid a personal price. A flying bolt struck him, resulting in the loss of an eyeball during the chaotic aftermath of the collision.

The story captured national headlines, attracting significant attention.

Despite being swiftly dismissed from the Katy Railroad that evening, Crush’s career took a surprising turn as he was reportedly rehired the very next day (possibly with a bonus!). He remained with the railroad until his retirement, accumulating an impressive 60-year career.

The Katy Railroad found itself settling lawsuits from victims’ families, including the injured photographer who lost an eye, receiving a settlement equivalent to $350,000 in today’s money. Some victims and their families were reportedly compensated with lifetime rail passes and cash.

The Katy Railroad reaped benefits from the stunt, gaining substantial national and even international attention. The orchestrated railroad collisions continued to serve as effective marketing tools in the subsequent years.

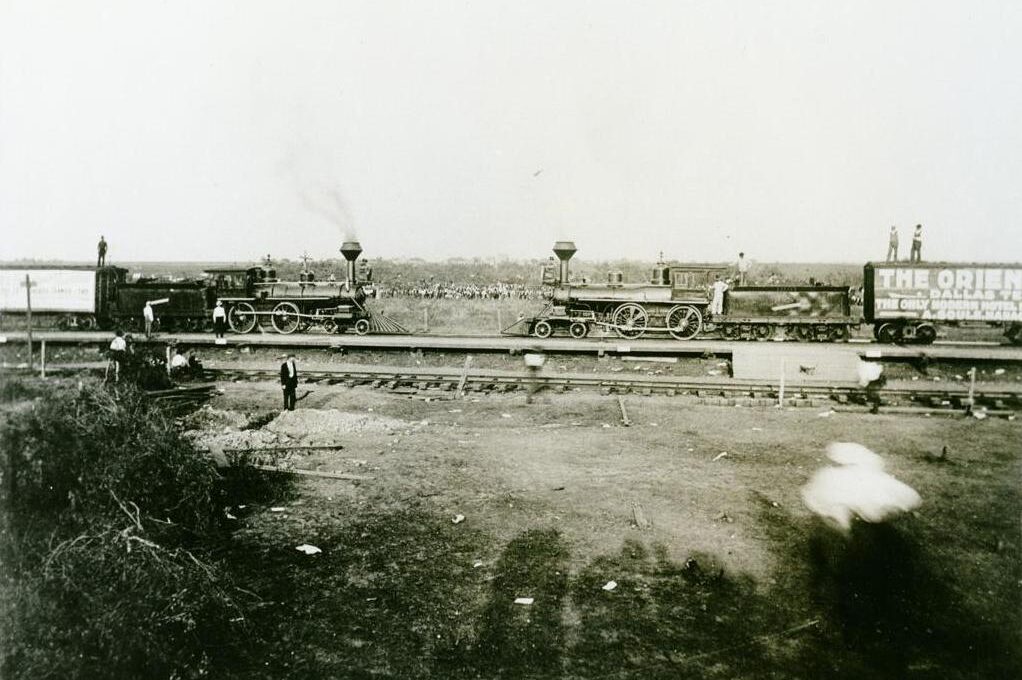

We initially thought the historical marker, numbered 5315, was located alongside the highway south of West, Texas. However, during our search, it was not found there.

Instead, we stumbled upon it near the historic Katy Depot in the heart of West, Texas, indicating that it might have been relocated.

Exploring the site of the collision, I used coordinates from Wikipedia to pinpoint the location, assuming their accuracy. Upon visiting, I observed a slight dip in the terrain, aligning with the described features, making me believe we were standing somewhere near the spot of the demonstration.

Given that it’s an active railroad, caution is paramount to avoid violating any laws during visits.

Imagining the historical scene with 40,000 spectators, a circus tent, carnivals, and vendors awaiting the spectacle, and then the ensuing chaos after the explosion, added a layer of fascination.

But the deaths, injuries, and sight of the crash didn’t deter the crowd’s curiosity. People were seen standing on the trains, exploring the wreckage.

Notably, the photo capturing this aftermath was taken by Deane, who lost an eye due to the exploding boilers. It’s impressive that he continued photographing despite such a challenging circumstance, considering the lengthy process of taking photographs during that era.

Publicity stunts sometimes carry risks, but rarely do they escalate to the extent of causing deaths and severe injuries. However, the late 1800s presented a different era, where such events were, to some extent, not uncommon for certain railroads.

It’s intriguing that the individual in charge faced immediate dismissal, only to be rehired the very next day, going on to establish a lengthy career with the railroad.

Surprisingly, despite the incident, other railroads persisted in staging similar collisions — it makes you wonder what lessons were learned from this episode.

Nevertheless, it remains an intriguing chapter in the history of Texas and one that was memorialized by Scott Joplin, the renowned ragtime music composer from Texas.

While it remains uncertain whether Joplin was among the spectators on that September afternoon in 1896, it is clear that the event left a lasting impression on him. At the age of twenty-seven, Joplin was so inspired by the crash that he composed “The Great Crush Collision.”

Interestingly enough this explosion in West, Texas would not be the most notable as another explosion in 2013 made national headlines.

Sources:

Waco History

Final word

In a world where content creators go to great lengths for views and likes, many of us can find a certain resonance with eras like the one in which events like the Crash at Crush Texas unfolded.

The willingness to take risks for publicity, while leading to a wild and unfortunate accident, mirrors some of the daring exploits we see today.

As a photographer, one of the most intriguing aspects of this story is the resilience of the photographer who lost an eye.

Despite the challenging circumstances and presumably navigating with only half his vision amid significant pain, he managed to capture the event and document its aftermath. Now, that’s dedication.

Daniel Gillaspia is the Founder of UponArriving.com and the credit card app, WalletFlo. He is a former attorney turned travel expert covering destinations along with TSA, airline, and hotel policies. Since 2014, his content has been featured in publications such as National Geographic, Smithsonian Magazine, and CNBC. Read my bio.