It’s easy to take credit reports and credit scores for granted. But could you imagine living in a time where even the idea of a credit reporting agency didn’t exist? How could you go about finding out if someone had a good enough track record for you to know that they wouldn’t vanish overnight after you shell out your cash to them?

Tip: Use WalletFlo for all your credit card needs. It’s free and will help you optimize your rewards and savings!

Humans have been borrowing from each other for thousands of years. Back in 3500 BC ancient Sumerians may have first issued loans for agricultural purposes in Mesopotamia and in Babylon around 1800 BC the Code of Hammurabi codified ceilings for interest on loans for grain and silver. (Interest has been a point of contention in many civilizations and outlawed as usury during periods such as the Dark Ages due to the belief that it was something God frowned upon.)

But determining the creditworthiness of others, at least in some sort of systematic fashion, is still a relatively recent creation. In early Colonial times, bankers and merchants didn’t have FICO reports to instantly pull so they had to resort to other more simplistic means. Neighbors and other counterparts would vouch for the character of the credit applicant and after checking up through the grapevine, bankers would then decide to issue credit. If Abitha, the local basket maker, didn’t think too fondly of you or your family, your hopes for opening up the next big tavern in town may have been over before they started.

This highly subjective method of determining creditworthiness was too inconsistent, and perhaps even more problematic, it lacked the sophistication to keep up with the increasing number of transactions that came along with the rise of industrialization. Lenders were being asked to extend credit to more and more customers who they lacked knowledge about.

In places like the UK this growth helped create the first efforts for credit checks. In the early 19th Century, English tailors started sharing client information with each other in an effort to find those clients who did not pay their debts. They even started the Marvel-esque sounding “Society of Guardians for the Protection of Tradesmen against Swindlers, Sharpers and other Fraudulent Persons” in 1826 in Manchester, England. But the British ran into the same issues as those in the U.S. — gossip and hearsay could go only get you so far. Eventually they needed much more. So in 1857, the Manchester Guardian Society appointed its first “data accuracy officer.”

Back in the U.S., folks began experimenting with different ways to accurately report credit and several credit reporting experiments were born. One of the most well-known of these experiments was the “Mercantile Agency” founded in 1841 by Lewis Tappan. Tappan was an abolitionist and Calvinist who actually had strictly opposed credit and lending money based on his religious beliefs but after experiencing harsh economic times and the “Panic of 1837,” Tappan realized that extending credit might be the only way to create viable business.

The Panic of 1837 had also taught Tappan how important it was to properly extend credit and accurately assess the creditworthiness of individuals. Luckily for Tappan he had built an extensive network across the country while being a well-known advocate of the abolitionist movement. This helped him to retrieve and store information about customers located throughout the nation. Tappan built up such a large database that other merchants reached out to Tappan for his data and his business began booming.

This method of collecting and storing data wasn’t met with open arms by everyone, however. Citizens accused Tappan of invading their personal privacy with his extensive file libraries but despite the criticisms the Mercantile Agency prevailed and by 1844 it had over 280 clients.

In 1849, Tappan retired and Benjamin Douglass took over the business. Ten years later, Douglass transferred the company over to Robert Graham Dun, who changed the “Mercantile Agency” name to “R.G. Dun & Company” and continued to expand business over the next few decades.

At the same time of this name a change, another powerhouse and rival was formed. In 1849, the John M. Bradstreet Company was founded in Cincinnati, Ohio, by a relative to American poet Anne Bradstreet. Bradstreet grew to popularity by publicizing the first book of commercial credit ratings known as the Dun Book. In 1857, Bradstreet published a highly detailed version of this book and the competition between the two firms picked up and in 1864, the former Mercantile Agency, R. G. Dun and Company, created an alphanumeric system that would be utilized for credit ratings for decades to come.

Thus, by the end of the Civil War the foundation was largely in place for credit reporting with commercial borrowers and by 1900 there were around 50 credit agencies operating in the US. But credit reporting focused on consumers was still not something that existed. But that would soon change, as the first credit bureau emerged near the end of the 19th Century.

In 1898, in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Cator Woolford created a list of customers that frequented his grocery store that he believed were worthy of credit and then he started circulating this list to other traders. The business soon took off into other industries such as insurance and even into international markets. By 1913 his company was re-branded as “Retail Credit Company, Inc” based in Atlanta, Georgia.

Around this same time, things were beginning to change as the Worker’s Rights Movement began and workers gained more rights along with increased wages. Merchants, including the automobile industry, wanted to cash in on the new state of the economy and so they began offering credit lines. in 1919, GM via GMAC started offering automobile loans and by the 1920s more than 20 percent of purchases made in US department stores were on credit, as things like appliances, furniture, and radios were becoming increasingly common to purchase with installment plans.

Credit reporting agencies like the Retail Credit Company were growing and more and more Americans were becoming more open to borrowing money based on credit to make purchases. But once again, security and privacy issues would rile consumers.

The Retail Credit Company didn’t just mine data on credit profiles, capital, and character, but it even delved into other aspects of borrower’s lives regarding things like political affiliation, marital troubles, childhood, drinking habits, and even sexual activity. It was even rumored that the RCC would reward its employees for finding dirt on consumers. (Could you imagine this going on today?) This led to a lot of resistance toward the RCC, especially when RCC announced they would be storing this information in these new contraptions known as computers, allowing for much more rapid transmission of such personal and at times damning information.

Alan Westin wrote in a 1968 New York Times article that, “transferring information from a manual file onto a computer triggers a threat to civil liberties, to privacy, to a man’s very humanity because access is so simple.” The outcry would eventually lead to the passing of the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) in 1970—a landmark piece of legislation that came with a host of rights. Notably, it forced credit bureaus to make their files public; remove data on race, sexuality and disabilities; and also remove negative information after a certain time period.

The circus surrounding the hearings and the passage of the FCRA is thought to have been so damaging to RCC that in the 1970s it changed its name from the Retail Credit Company to a company called Equifax, as it is now known today.

Back in the 1950s another credit reporting agency was coming into existence. Two of the most famous aerospace engineers, Simon Ramo and Dean Wooldridge had been leaders on the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile program established in response to threats from the Soviet Union. These two visionaries believed cashless payments were the way of the future and knew they could apply their scientific and technological knowledge to commercial markets to determine individual creditworthiness in order to effect such payment methods. Despite the voices of many skeptics, they worked out a deal with Thompson Products in order to obtain the needed capital and formed a joint business known as “TRW.”

TRW used some of the most talented software engineers in the US to catch up to their competitors like the Retail Credit Company and in 1968 they entered the credit reporting industry with the acquisition of San Francisco-based “Credit Data.”

(1968 was also the yearTransUnion formed as a holding company for a railroad leasing organization. A year later TransUnion acquired the Credit Bureau of Cook County, which maintained over 3.6 million card files giving TransUnion the jump start it needed to compete in the market.)

TRW’s technology-driven approach accelerated their growth while allowing TRW to remain accurate and effecient with their handling of credit reports. Some even have referred to TRW as the “Google of their time” because of their powerful informational databases used for things like targeted marketing. By 1986, TRW had become the first credit agency working in all 50 states, although RCC AKA Equifax was hot on its trail.

TRW, later known as TRW Information Systems & Services (TRW IS&S) experienced some mighty struggles in the early 90s during the recession period but they pulled out of the recession with innovative projects like “File One” which helped better consolidate credit records. In 1995, after battling for years through economic struggles,TRW IS&S decided to put the company up for sale and two private equity firms purchased them. They came up with a long list of potential names like Actua, Cogneo, Factbase, Fidelta, Informedia, Knosis, Newlight and Trustin but ultimately settled on one: Experian.

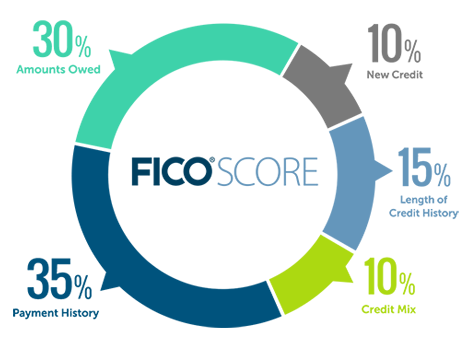

So all three credit bureaus were now born in the US: Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion. But as the big three emerged, there were still glaring differences between the credit reports and a pressing need for better accuracy and consistency given the growing markets for credit. And this is when FICO came in.

[Part II will continue with the History of FICO Scores]

Daniel Gillaspia is the Founder of UponArriving.com and the credit card app, WalletFlo. He is a former attorney turned travel expert covering destinations along with TSA, airline, and hotel policies. Since 2014, his content has been featured in publications such as National Geographic, Smithsonian Magazine, and CNBC. Read my bio.